Written by Isra Saleh

Source: Al-Manssa website

”They dressed me up and took me to the room”… How Do Underage Girls Learn About Marital Relationships?

Twenty-year-old Olfat Al-Husseini* recalls the first time she was forced to have sex after being married off before she was 15 years old: “They dressed me up and took me to a room and told me, ‘Don’t do anything and let him do whatever he wants,'” she said.

Even after her divorce four years ago, Olfat is still suffering from the negative effects of being married off as a child. She is trying to focus on completing her studies and is considering undergoing psychological therapy. She says, “I can’t imagine going through that experience (marriage) again, neither by my own choice nor against my will.”

Although she still lives with her family, she plans to become independent and leave the environment where she was abused, the abuse which led her mother to separate from her father, because he forced their daughter into this marriage.

She tells Al-Manssa, “I can coexist with my mom and siblings, but not in a normal way. Many times, I feel like I can’t adapt, even though they weren’t really involved in the matter.” She also feels sorry for girls facing a similar experience, saying, “I wanted to decide how my life would go. I didn’t want to be forced into anything.”

Article 31 bis of the Civil Status Law criminalises marriage of girls under the age of 18, but “legal loopholes have left room for circumventing the law by marrying early with an undocumented contract, in addition to the lack of mechanisms to deal with the issue of forcing young girls into marriage,” according to the National Strategy to Reduce Early Marriage 2015-2020, issued by the National Population Council. The strategy also noted that provisions to “criminalise and fine those responsible for depriving a child of education are not enforced.”

A Relationship by Coercion

Olfat recalls how she only wanted the life of an ordinary student like those her age, but her father forced her, saying, “We don’t ask girls for their opinion on marriage.” When a suitor came forward who hadn’t completed his middle school education, worked as a barber, and used drugs, her father agreed without asking her.

Before the wedding, Olfat, who had received an Azhari education, knew only the rules of marriage, such as the engagement and public declaration of the marriage. “For the first two days, I didn’t understand what was going on, and when he tried, I refused, until he told my parents and they intervened,” she recalls.

She adds, “It was really difficult… I didn’t understand what was happening to the extent that even when he was reaching sexual climax, I didn’t understand what it was. I thought he was urinating on me. I didn’t know those were sperm.”

Olfat emphasises that she never consented to any sexual relationship with her ex-husband: “For me, the whole thing was coercion and I was forced and I had no right to say yes or no.” But every time she expressed her refusal of the relationship, her family’s response was, “Let him do what he wants so that God doesn’t hold you accountable and the angels don’t curse you.”

No Punishment.. No Prevention

Olfat remained trapped in that marriage, waiting for her 18th birthday to be able to prove her marriage first in order to then be able to get a divorce. In the meantime, she was under constant pressure from her family, arguing that “the one who you are exposed to is better than others, and you don’t know who will accept you after this when you’re divorced.”

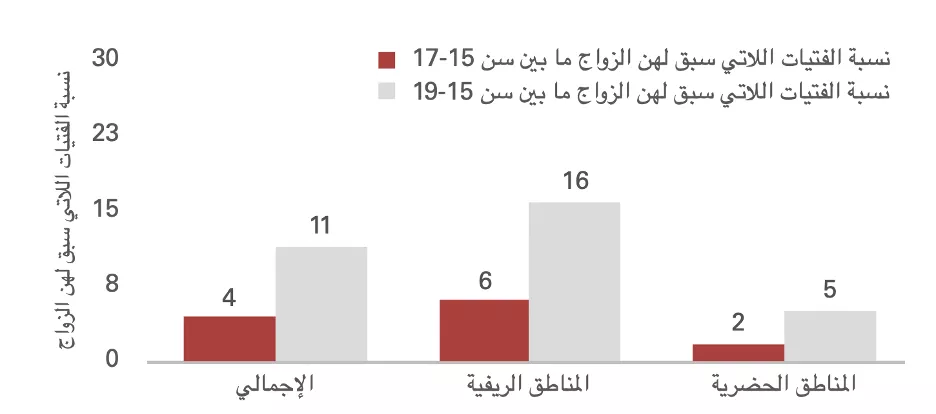

Olfat is not the only one. Besides her confirmation that many girls in her village in Dakahlia Governorate were married in the same way, a policy paper on eliminating early marriage, issued by the National Council for Childhood and Motherhood, indicates that “according to 2017 data from Egypt’s census, child marriage remains a persistent issue in Egypt. Nearly one in 20 girls (4%) in the age group 15-17 years and one in 10 (11%) adolescent girls aged 15-19 years are currently married or have been married before, with significant disparities between rural and urban areas.”

Marital rape

Olfat’s story is similar to that of Zeinab*, who recalls, during her conversation with Al-Manssa, being married off to her cousin, “the successful one who earns a lot of money “, when she was in the third grade of middle school.

Zeinab also knew nothing about sexual relations, and her ideas about marriage were limited to “the white dress, the house, the new clothes, and putting on makeup, which was the peak of the dreams at her age.” She comments, “I used to see them on TV kissing and having children, so I thought it was that easy.” But the wedding night did not go as easily as she imagined.

She says, “After the wedding, I walked in and I couldn’t understand why they started arguing because he wanted to consummate the marriage in a certain way. My mother was yelling, asking why and where she had gone.” She continues, “After they left, he was like a bull—really, like a bull who has finally found a prey.” She describes the scene, which involved not only beating and humiliation but also rape.

Zeinab was shocked to see a naked man for the first time, “It was a horrible sight for me, I kept closing my eyes and hiding.” But the hunter did not leave his prey until he completed his mission in a moment she compared to death, “I felt like I was dying like they were taking my soul.” She adds that four days later, she developed vaginismus, a vaginal cramp.

The child went to the doctor, who advised her not to be afraid, and prescribed her nerve-calming sedatives to allow her husband to continue his violent practices, “What could the doctor say when even my family didn’t care?”

The husband used to beat Zeinab for sex, calling her cold until she developed her refusal skills by dyeing sanitary pads with Betadine to prove to her husband that her menstrual cycle was preventing her from having sex with him. But when it was repeated, he asked her to visit the doctor to stop it.

Zeinab’s luck was worse than Olfat’s due to the length of her experience. “I stayed married for 10 years and saw hell,” Zeinab recalls. She remembers that she didn’t find anyone to support her in her continuous attempts to divorce. Her father pressured her to return to her husband, who exploited the fact that their marriage was undocumented to humiliate her.

During that time, Zeinab tried to commit suicide because she felt so oppressed in the marriage, in which she had two children, one of whom is autistic. She eventually got a divorce four years ago, and until now she does not know how her marriage and divorce were officially documented.

Nagwa Ibrahim, the Executive Director of the Edraak Foundation for Development and Equality, believes that child marriage is a form of sexual violence that should be punished by the law as a rape crime, in addition to being “a form of human trafficking.”

Despite the fact that the percentage of women who have experienced any form of sexual violence from their current or former husbands reached 5.6% in 2021, according to the latest health survey by the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics, Egyptian law does not criminalise marital rape, regardless of the legality of the marriage.

For now, Zeinab is content with raising and caring for her two children and does not wish to remarry. “I’m sick of them all; they’re all disgusting. How will the next one be any better? They’re all the same.” Therefore, she wears a “fake” wedding ring so that no one would know that she is divorced, “so that no one will covet me and say that I am lonely.”

Love Is Not Enough

Unlike Olfat and Zeinab, Somaya* got married “for love” when she was fifteen, but that didn’t prevent her from suffering. Now 24 years old, she confirms that her early marriage was a mistake, she hopes others won’t make.

She says, “I wanted to continue my education, but he refused, and because I loved him, I listened to him.” At the beginning of her story, Somaya mentioned that her husband did not force sex on her, but “he took her with reason and persuasion” at the start of the marriage, so she says that she did not refuse a sexual relationship with him.

However, as the conversation continued, she began to open up more and more, admitting that he sometimes hits and abuses her during sex, especially when he is “upset or angry.” But he calms down and comes back to her with sweet words, so she remains silent and overlooks the violence she is subjected to. “Otherwise, I would have to divorce him and go back to my father’s house and be upset?”

In an authentic Upper Egyptian dialect, she says, “I stay with him; when he says a sweet word, I am content. Sometimes he hits me and shoves me, and then after a while, he says a sweet word to appease me.”

Nagwa Ibrahim comments that a girl’s consent may come after the idea of marriage has been embellished for her by her family and solidified in her mind, just like the rest of the girls in the village or family. Therefore, the fact that girls do not reach the age when they are fully and freely capable of making their own decisions without coercion violates the conditions for full and informed consent.

Lawyer Heba Adel agrees, stressing that the law does not allow the marriage of a girl under the age of 18 to be documented. Therefore, her consent to the marriage is not considered valid, as she is still a child in the eyes of the law and does not have full capacity.

With the mind

Recently, Edraak Foundation for Development and Equality launched the “Marriage with the Mind, not the Body” campaign, coinciding with the proposal of a law to criminalise child marriage in the House of Representatives. According to the foundation’s director, there are three draft laws submitted in addition to the one submitted by the government to criminalise child marriage.

During the discussion of the law in parliament, it was stopped by the legislative committee, which sent it to Al-Azhar for its opinion, but no response has been received so far.

If Alfet’s experience ended with her gaining her freedom and addressing the effects of that marriage, Samia, who moved with her husband from Minya to Cairo, is forbidden from leaving the house except at specific times and for reasons her husband deems legitimate.

“Until now, I still regret that I left my education,” she comments. Based on her experience, she emphasises that girls should complete their education, saying “There is nothing better than education.” She adds that marriage is “a very big responsibility” that a young girl cannot bear, even if she wants it, “they don’t know what will happen afterwards.”

(*) Pseudonyms are used to protect the privacy of the sources.